ELINOR ZAROUR SHALEV

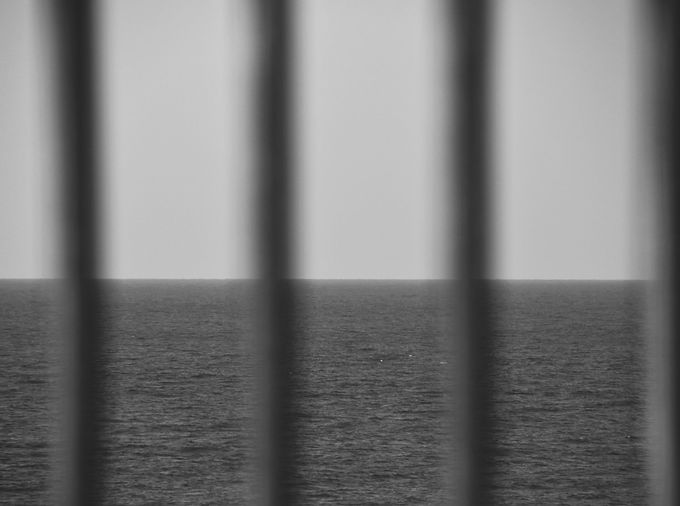

The fence between us הגדר ביני ובינך

היצירה עוסקת בגבול שבין הנוכח לנעדר, בכמיהה, ובערגה לאור המציאות.

שם היצירה 'הגדר ביני ובינך' הינו בזיקה לשירו של רבי שמואל הנגיד 'הים ביני ובינך', שירת קינה על אחיו הבכור, כאשר 'הים' משמש דימוי לפער הבלתי ניתן לגישור בין הנוכח לנעדר, בין עולם החיים ועולם המתים. בצילומים הגדר בתפקיד הים החוצץ שבקינה, והים בתפקיד אחיו הבכור הנעדר של רבי שמואל הנגיד.

המבט לים הינו החיבור הקלאסי לרגש האוקיאני, לאותה תחושה עילאית של חיבור גוף ונפש, פליאה, התחדשות מתמדת, יראה, והכרת תודה. תחושה זו עולה למראה מרחבי האינסוף העוצמתית שהים מביא עימו. הים מאחורי גדר מעלה פרדוקס ואת ה'ריב' ההיידגרי שמקורו בתסכול ותחושת אסירות המעצימה את כמיהת הנפש לנעדר, לחופש, לשלמות, אשר נראים כל כך קרובים ועם זאת בלתי מושגים. ומאידך גיסא, ה'ריב' ההיידגרי בעולמו של רבי שמואל הנגיד, הים כדימוי לתווך עצום מלא סכנות ואי-וודאויות, הים כתהום נשיה ובעתה, כחוצץ בל יעבור.

קו האופק, כגבול רחוק של הפרדה עדינה, נצחית ואינסופית בין מים לשמים, בין חיים ומוות, מקבל משמעות הפוכה בעת שמתלכד ומתכסה בקורת ברזל גשמית של סף גדר נוקשה ומגבילה. החפיפה בין האופק והגדר מחברת בין הרחוק והקרוב, בין הנוכח לנעדר ומרמזת שהים, אם כסכנה ואם כנחמה, מחובר בעבותות לכאן ועכשיו, ומעצים את תחושת הנכספות, הערגה, הגעגועים, הבלתי מושג והנעדרות.

המיקוד המשתנה בין הים והגדר משנה ומעצב את מערכת היחסים בין כאן ושם. כשהסורגים מטושטשים, מראה הים המושלם ברור ומזמין. עם זאת קיים מכשול מטושטש המפריע לצופה. המחשבה נישאת אל האופק אך הגוף חייב להשאר מאחורי הגבול. לעיתים נדמה לנו שהגדר אינה קיימת ושהצלחנו להרחיקה מאיתנו עד שהתלכדה עם גלי הים ונעשתה לחלק מהם. עם זאת, למרות כי נראית שהורחקה ונטמעה, הגבול שריר וקיים.

במחשבה אחרונה, נשאלת השאלה מיהו הנעדר? האם העין שמאחורי עדשת המצלמה היא הנעדרת מעבר לגדר? או שמא ההיפך הוא הנכון, הים והחופש הם אלה הנעדרים, הכמהים, המוגבלים בגדר.

The name of the work 'The fence between me and you' is related to Rabbi Shmuel HaNagid's poem 'The sea between me and you', a poem of lamentation for his elder brother, where the 'sea' is used for the unbridgeable gap between the world of the life and the world of the death. In the present work, ‘the fence’ in the role of the ‘sea’ in poem, and ‘sea’ in the role of the elder brother of Rabbi Shmuel HaNagid.

The changing focus between the sea and the fence reflects the relationship between here and there. When the bars are blurred, the picture of the perfect sea is clear and inviting. However, there is a blurred obstacle that hinders the viewer. The thought is carried to the horizon but the body must stay behind the border. Sometimes it seems to us that the fence does not exist and that we managed to move it away from us until it merged with the waves of the sea and became part of them. Even though it appears to have been removed and assimilated, the border is strong and exists.

Sea viewing is the classic connection of the supreme feeling of body and soul connection. This feeling arises in the same breath with the powerful sense of freedom that the sea brings with it. The sea behind a fence brings up a paradox and the Heideggerian ‘conflict’ that originates from frustration and a sense of imprisonment that intensifies the soul's longing for freedom and perfection, all so close yet unattainable.

The horizon line, as a distant boundary of a subtle, eternal and infinite separation between water and sky and between life and death, takes on the opposite meaning when it is fused and covered with a physical iron beam of a rigid and limiting fence threshold. The overlap between the horizon and the fence connects the far and the near and suggests that the sea, whether as a danger or as a comfort, is thickly connected to the here and now, intensifying the sense of terror and conflict.

In a final thought, a question arises, who is the prisoner? Is the eye behind the camera lens imprisoned beyond the fence? Or is it the opposite, the sea and freedom are those who are imprisoned, longing, limited by the fence.